Excerpts from The Accessibility Operations Guidebook

From the introduction

This book has two parts.

Part 1: Theory is a crash course in theories and frameworks I’ve found to be useful in understanding and doing this work. Chapters in this section are about burnout, education and literacy, organizations, communities, and intersectionality and disability. None of these chapters are exhaustive. They are designed to get you thinking about ideas you might not have considered before, and to give you the vocabulary to dive into your own research.

Part 2: Practice is about the practice of doing accessibility work. It’s about operations, communication, services, program management, and planning. This section will (hopefully) help you consider the types of activities you can do based on your needs, resources, goals, and the ways you want to grow your practice.

From Chapter 3: Accessibility literacy

When I first started thinking seriously about how to teach accessibility, I found myself returning to information literacy again and again. I’d been doing this in my head for years but hadn’t really pieced together why or how. I finally ran with this idea for a talk called “Designing Accessibility Education in Organizations” that I gave at Accessibility Toronto Conference in 2019. A document version of this talk appears in the resources for this chapter. I coined the term “accessibility literacy” then, and the label has stuck for me. From that work, I’ve developed the Accessibility Literacy Framework (ALF).

What this tool is

I based ALF on my experience using the Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education. As a Constructivist framework, ALF is intended to help you understand how engaged people are in their own accessibility learning and practice. Having that knowledge will make it easier to engage with them on this topic.

ALF has two main uses:

First, measuring an individual’s accessibility literacy. For people to be able to solve most accessibility problems on their own, they need to learn how to find, evaluate, and use information. If we can measure this, we’ll have some idea of what they’re capable of in an accessibility context.

Second, measuring an aspect of the success of your program. If we can measure literacy for individuals, we can use improvements of literacy at scale as a measure of success for our practices over time. If we can demonstrate that people are getting better at accessibility literacy, we can tie that to the value of accessibility education and knowledge management. You can use this tool alongside others to track how your program changes the organization over time.

What this tool isn’t

ALF is not a tool for measuring expertise. We don’t need to make more accessibility experts. What we need is for non-experts to get better at integrating accessibility information and literacy into their work. We need them to be able to make informed decisions without the constant intervention of an accessibility practitioner.

Frames

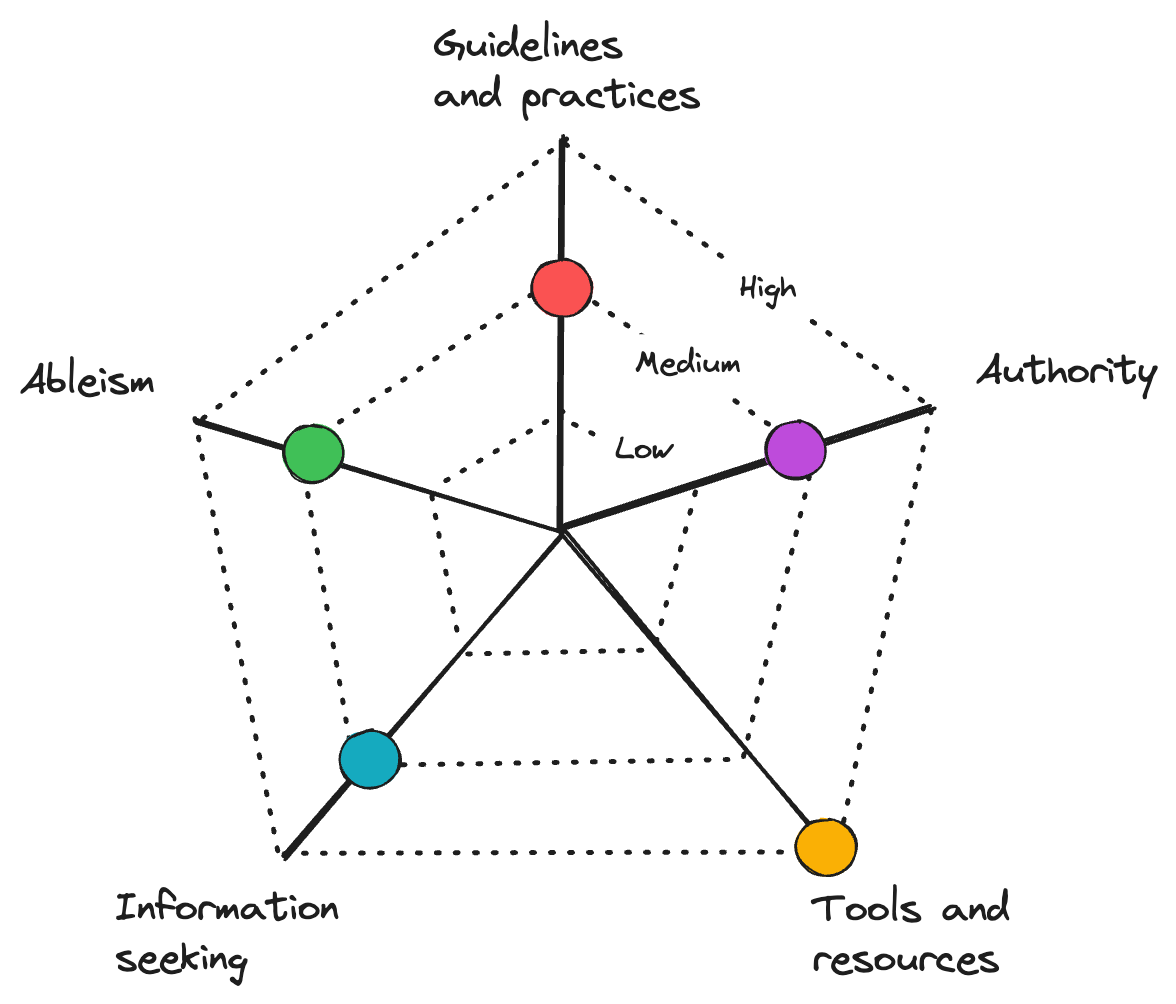

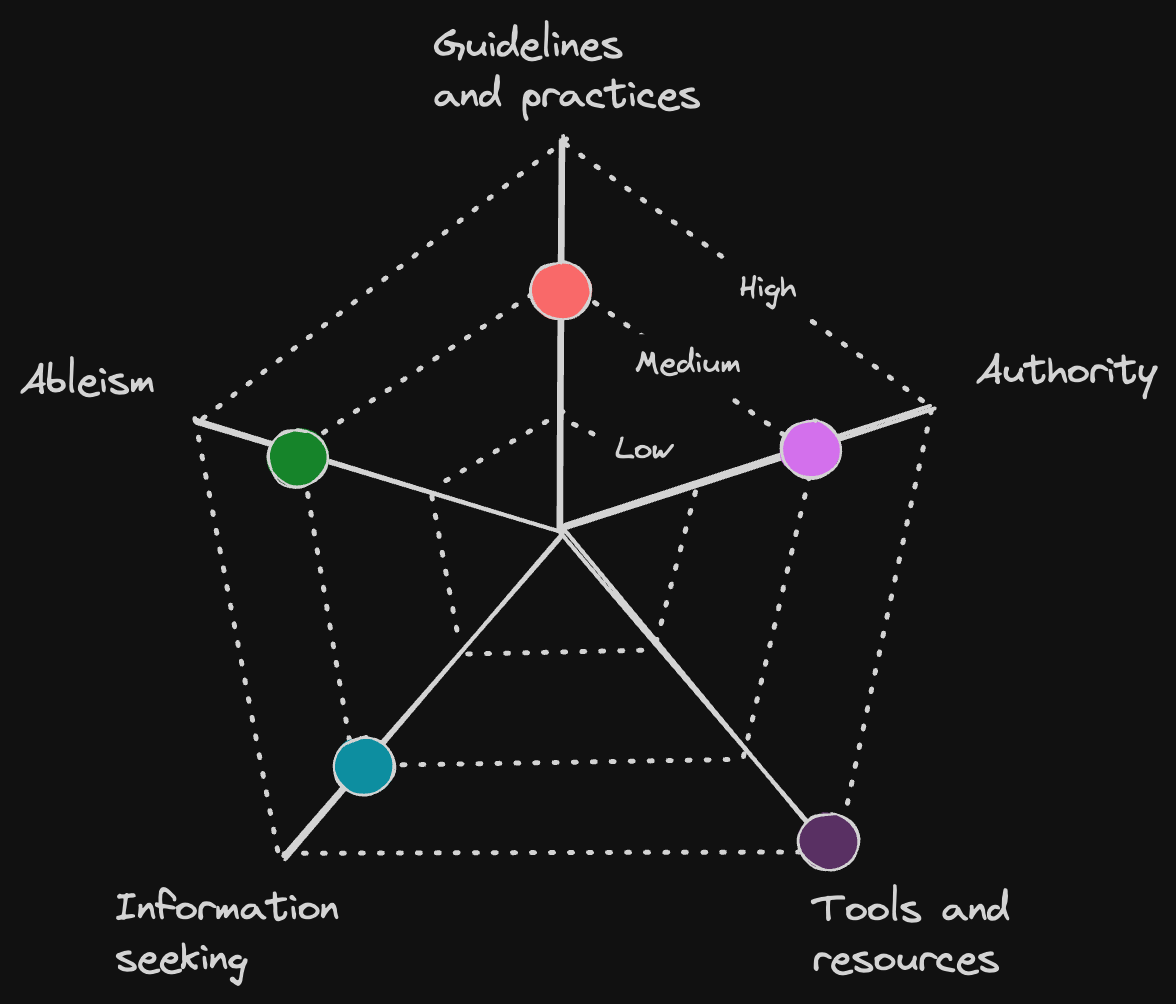

ALF has 5 frames. They capture different facets of how accessibility literacy fits into people’s work. You can use fewer or more frames, or make your own to fit your needs. The frames are (in no particular order):

- Guidelines and practices

- Authority

- Tools and resources

- Information seeking

- Anti-ableism

Guidelines and practices

How familiar is a person with the accessibility guidelines and practices that impact their work and organization? Can they:

- Find the guidelines and practices that affect their role and responsibilities

- Evaluate which guidelines and practices are appropriate for a given feature or project

- Use guidelines and practices effectively in their work

Authority

How does a person seek help from authorities (experts) in the field? How do they decide who is an authority? How do they consider an authority’s motives, lived experience, and area of expertise? Can a person:

- Find information from experts in the field

- Evaluate an expert’s authority and understand their experiences and motives

- Use information from experts appropriately

Tools and resources

How familiar is a person with the accessibility tools and resources in their organization? Can they:

- Find accessibility tools and resources for their role

- Evaluate what tools and resources are appropriate for a given feature or project

- Use tools and resources appropriately in their work

Information seeking

Knowing how people do their own research is critical to understanding what decisions they are going to make. How does a person do at their own accessibility research? How skilled are they to:

- Develop relevant research questions

- Evaluate and adjust their process as they learn new information

- Know when they have enough information to make a decision

Anti-ableism

How aware is a person of ableism and its impacts? Can they:

- Understand how ableism intersects with other axes of oppression

- Evaluate biases about ableism, accessibility, and disability (including their own)

- Use their accessibility literacy skills to do anti-ableist work

From Chapter 9: Communication and coalition

Identifying helpers and adversaries

Any sort of change management work is going to come up against people with different levels of enthusiasm. If you think back to Chapter 4: Organizations, you’ll recall that people come along for change in several phases across a bell curve. Some people are bought-in immediately. Others take time and only join kicking and screaming.

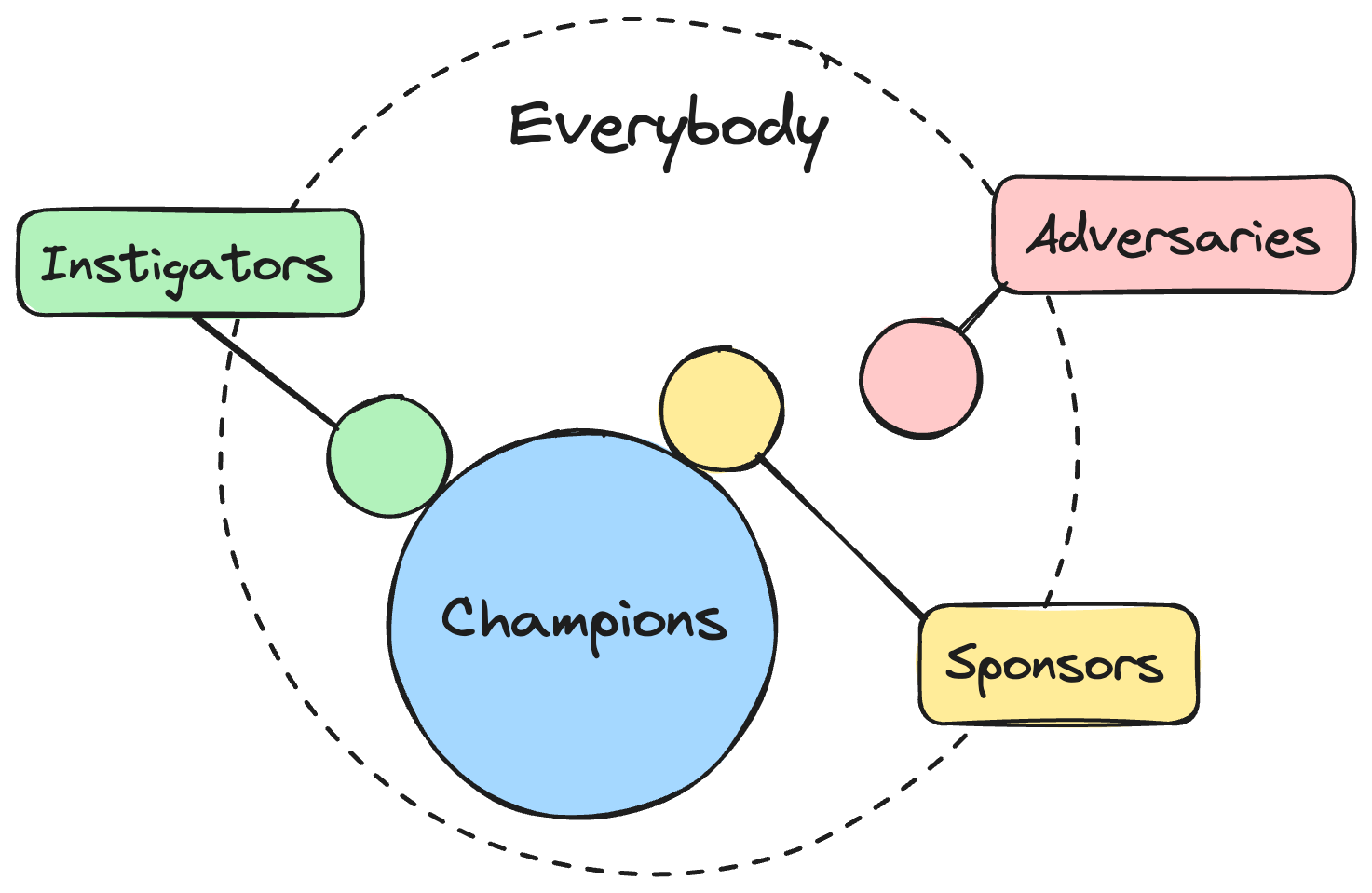

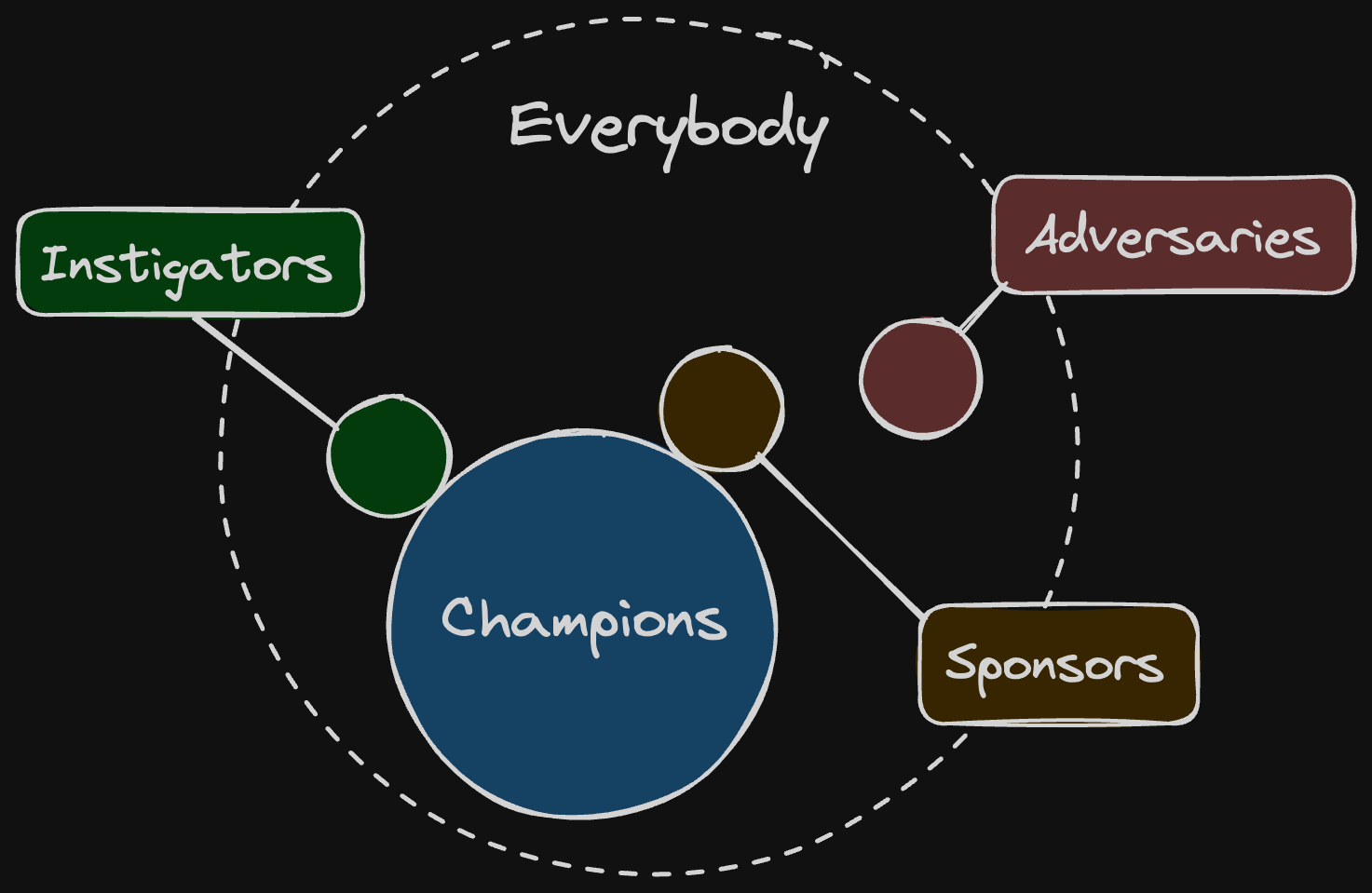

I think it’s important to consider when people come on board. It’s also important to consider what people become in this work. Wherever you are in your work, you will also establish relationships with different people. As an instigator, you are forming a web of connections. Some will want to help you in the day-to-day work, and others will be able to provide support from afar.

We already talked about different ways to organize other workers in relation to change management. I’d like to propose a few categories or roles of what people become in the work to help us think about what they can best do to help with the work. First let’s talk about people who can help us.

Instigators

Instigators are your most involved helpers. They are your comrades. They have your back and aren’t interested in doing the work performatively. These are the folks you vibe with regarding this work, and who you can be more honest and collaborative with in your communication. They will most likely be ICs, but they may also be PM/POs, people managers, or directors, as well as people from internal teams like DEI, knowledge management, or people that work in user-facing roles, like customer support. You may find them early in the work as co-instigators, or you may find them as you go.

Champions

It’s pretty standard at this point to call a group of pro-accessibility folks a champions network or similar. These are people who aren’t collaborating with you day to day, and don’t have traditional power in the organization, but are somewhere in between. Champions carry the message to their teams, so they may be your primary connection to some teams and projects. Accessibility is part of their job, but they don’t make it their job.

Sponsors

Sponsors are a bit further removed, but they are still supportive. They are most likely senior individual contributors (ICs), project/program managers or product owners (PM/POs), and directors, people with some level of traditional power in the organization. These are the folks who can sign off on a pilot program or be a sponsor for a community of practice. They help enable the work but aren’t in it day to day. Your relationship with them is a bit more formal, so communication should reflect that.

People who legitimately care about the product and have the authority to leverage that care can become excellent sponsors even if they aren’t personally invested in accessibility work. If they think of accessibility like security or localization, they’re sponsor material.

Adversaries

Occasionally you will run into a person who actively works against your efforts. I don’t mean that they drag their feet. I mean they actively push back. They consider accessibility a waste of time and money and think the same thing about other DEI efforts. Typically, these are not folks who back any “progressive” cause in any real way. The common denominator for them is that these things don’t make money, and therefore they are not worthwhile.

In a best-case scenario, the simplest thing we can do is just not engage with bad actors. If there are power lines that flow around that person instead of through them, those are probably better options for you. This gets very difficult when that bad actor is your manager, or your director, or your CEO, though.

Odds are, if they are truly against what you’re trying to do, they are against similar work that other people are trying to do around equity, belonging, and making the organization more stable and hospitable. There are probably other people they’ve pissed off, and those people might be good collaborators.

Sometimes it’s only possible to make progress in part of the organization, based on how it’s currently organized and based on how much energy and power you have. And that’s okay.

From Chapter 11: Overview of a program

“Devon,” you are thinking. “You spent a whole chapter telling me that operations is a better model than traditional program management for accessibility. Why are you telling me about programs now?”

In short, operations breaks some of the rules of program management, or at least puts a different spin on them. A traditional program often comes down to doing things for other people. Operations is about enabling other people to do those things largely themselves. To understand what rules to break and when with operations, you need to understand what those rules are doing for a program in the first place.

What’s a program?

A program is a collection of activities organized around a goal or need. Programs do three main things:

- Take investments of resources and information

- Bring people together to do activities

- Capture and measure data about those activities

If you don’t like words like “investments” and “resources,” you can think of a program as a set of interrelated experiments. You make a hypothesis, conduct experiments, and then see if the results match your hypothesis.

The person who coordinates a program is usually a program manager. The program manager usually works with other people who take on other roles, like project managers, team leads, and subject matter experts (SMEs). If the program is larger, it might also have product owners and people who manage SMEs by discipline, like a design manager or an engineering manager.

But that’s where things get messy in the accessibility field. In a normal program, the program manager may do extra tasks occasionally. But they usually aren’t also running all the activities, reviewing all the data, and being a subject matter expert, all the time. However, people expect accessibility practitioners to be subject matter experts, legal experts, designers, engineers, researchers, educators, and program managers, among other things. It’s a pattern that’s familiar to overachievers. You do so well at something that you get a reward, and that reward is more work. If you make enough noise about accessibility, you are rewarded with doing accessibility. All of it. Congratulations?

People outside our field almost never understand this, so let’s describe what an accessibility program usually is.

What’s an accessibility program?

An accessibility program is usually one or more people working to help an organization do ongoing accessibility work. It might be an official program, where someone has “program manager” in their title. It also might be completely ad hoc, with people who have no formal or informal training in either accessibility or program management. It might form in reaction to an event like a lawsuit. Or it might be more proactive. Or both at once.

These programs do many things, based on what’s possible in their organization.

In large organizations with long histories of legal compliance around accessibility, accessibility programs might be very well established. There may be a centralized program connected to accessibility teams for different divisions or connected to embedded practitioners in different product teams. In an organization that doesn’t have that type of history or established structure, there might not be a program at all.

You might be trying to start that program. You might be the program already.

When to consider building a program

You may have been told by someone in management or leadership that you “have” to build a program, or the nicer version, you have an “opportunity” to build a program. In which case: Sorry, and congratulations!

If you are already providing two or more accessibility activities or services, you are already, technically running a program, by definition. Sorry, and congratulations!

If you aren’t already running a program, a good time to start one is when you feel like you have grassroots support. That is, when the organization climate is pro-accessibility. Ideally the organization culture isn’t actively hostile to accessibility, but you can do this work in any case.

If you’re worried about your bias and you aren’t sure if grassroots support is there, one of your first activities should be to learn about people’s attitudes about accessibility, which we’ll talk more about in Chapter 12: Organizational needs.